* Noble or landrace?

* Roy Farms & Abstrax

* Good news from England

* Hop profile: Callista

* Additional reading

– New carbon footprint chart

– BarthHaas 2023 Harvest Guide

Welcome to Vol. 7, No. 11. Thanks again to Best of Craft Beer Awards for sponsoring Hop Queries, and to readers who have made individual contributions.

YOU SAY “NOBLE” — I SAY “LANDRACE”

Last month, I promised to write about “Old World” and “New World” hops, figuring I would consider if the terms tell brewers anything meaningful. Turns out, some background is needed. That first, then next month a look at why molecular markers may be useful when examining where new and old worlds meet.

Not surprisingly, the story that started this off suggests the “most important of the [Old School] bunch are the four ‘noble hop’ varieties varieties used to make pilsners and lagers: Hallertau Mittelfrüh, Tettnanger, Spalt, and Saaz.”

You might be nodding in agreement, but I am shaking my head. In “The Oxford Companion to Beer,” Adrian Tierney-Jones writes, noble hops is “a term that has an undeniable ring of antiquity and distinction to it, yet is merely a marketing tag and a recent vintage at that.” And, “Today there is no longer any agreement as to which hops do and do not belong to the lofty ranks for Humulus lupulus nobility.”

Tierney-Jones spoke with German hop scientists Adrian Foster before writing the Oxford Companion entry. What Germans called “fine aroma hops” in the 1970s sometimes became known as “noble aroma hops” in other languages, and neither term was ever officially defined, Forster explained to me in an email. “Therefore, not all brewers and hop merchants have the same understanding of which hop varieties rank among fine aroma hops.”

Beyond the four listed above, others would add Hersbrucker Spät from northern Bavaria and Strisselspalt from the Alsace region of France. All six are products of natural selection, each having emerged by the 19th century as an essential ingredient in beer for which brewers would pay a premium price.

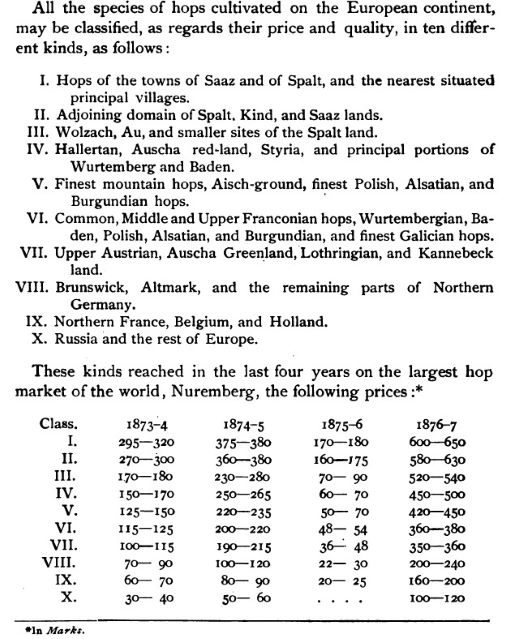

A page from “Hop Culture in the United States” (1893)

Hops traded in Nuremberg, the continent’s largest market, were classified into 10 groups, based upon where they were grown. Those from the towns of Saaz and Spalt commanded the best prices, which could be six to eight times more than those from the least desirable regions, such as Russia. There is no indication nobility was part of the equation.

Earlier, Der Praktische Gutsvewalter (“The Practical Estate Manager”), published in 1846, discussed the evolution of Edelhopfen, the varieties that would be cultivated and sold to brewers, from wild hops. Nearly a century later two English hop scientists translated edel as noble. They had other choices: fine, precious, and of a good family. Any would have been acceptable.

Hop geneticists refer to the varieties that farmers chose to propagate over the course of centuries as landrace hops. Val Peacock, long-time manager of hop technology at Anheuser-Busch and now a consultant, explained the decision was pretty basic. “We like the hop that grows on this side of the road. We’re not so happy with the hop that grows on that side of the road.”

By the 1970s, those in the hop trade sought ways to categorize varieties with a much wider range of characteristics than in the past. “Fine aroma hops” emerged as a term to distinguish traditional, some would say classical, varieties from the new cultivars. In Asia and North America, Forster wrote, marketers introduced the term “noble aroma hops.” Some brewers shortened that to “noble hops.”

Breeding programs exist not only to create varieties with more exotic aromas and flavors, but to find ones less vulnerable to disease and climate change. Newer cultivars such as Saphir and Diamant have been bred at the German Hop Research Center as potential “fine aroma hops.”

Yes, the big four — or five, or six, depending on who is making the list — remain the standard that breeders compare new hops to. But they are not the only landrace hops still being harvested. Most notably, the two best known English hops, Fuggle and Golding, have much in common with the continental landrace varieties.

I prefer the word “landrace” to “noble” because it is more encompassing. The more diverse the population of hops that breeders have to draw from, the more diverse the selection of new varieties brewers will be able to choose from, whether they are seeking old world or new world flavors.

ANOTHER AROMA-FOCUSED EXTRACT: QUANTUM BRITE

Roy Farms has a new twist on “No People. No Farm. No Hops,” a phrase the company has trademarked. The tagline on the page with information about the Quantum Brite hop extract products (scroll down) from Abstrax that Roy is now distributing is “No People. No Farm. No Terps.”

That’s “terp” as in terpenes.

Abstrax Tech, already well known for its botanically derived terpene blends and isolates that are native to cannabis, officially launched its hops division last May. The company offers multiple products, such as its Brewgas Series. That one includes offerings such as Pineapple Express and King Louie XIII.

They pack a punch. Writing about Seventh Son Pineapple Express for Craft Beer & Brewing, Kate Bernot began: “Once you get a whiff of this beer, you understand why the brewery has to say explicitly that it contains no THC. This pineapple sour is brewed with cannabis terpenes that are, yes, pungent.”

Quantum Brite, in contrast, is produced entirely from hops, using a proprietary extraction technology, and is designed to offer true-to-type aroma. It is described as “fully soluble, efficient, easy to use and clean up; flows well and won’t stick to or require special equipment.” It is one of several similar relatively new products. I have written a story for Brewing Industry Guide about research that compares such products to pellets, but I have not seen work that compares the products to each other.

Roy Farms has 15 varieties on offer, including two experimentals from Latitude 46°, a breeding enterprise between Roy and Green Acre Farms formerly known as ADHA. Most are grown at Roy, but choices also include cultivars from the southern hemisphere. They are not sold by name, but by IHGC hop codes. Thus, CHI is Chinook, NRN is Nectaron, etc.

DATELINE ENGLAND

– A collaborative project between University of Kent researchers and Wye Hops—along with the National Institute of Agricultural Botany (NIAB), the British Hop Association, The Hop Plant Company and LGC genomics—has been awarded more than a half a million pounds to develop environmentally resilient “super hop” varieties.

The five-year project will involve Helen Cockerton, industrial research fellow at the university’s School of Biosciences, working closely with hop breeder Klara Hajdu on genetic informed breeding to create hop varieties which are more resilient to drought, pests, and diseases.

Peter Darby, Hajdu’s predecessor at Wye Hops, explained via email that she “realized that to achieve some of her aims in molecular science of hops, she needs to develop a partnership with academic institutions and companies who can supply the lab-based facilities she needs. Wye Hops is entirely field-based. . . . In Helen Cockerton she has found a partner who is interested in hops and has an impressive record for securing funding.”

– This is not the only program in play. Although hop merchant Charles Faram just struck a deal to distribute Yakima Chief Hops advanced products as well as hops, the company has also developed and released several varieties in the past half dozen years. More are in the works.

“UK hops for UK breweries is definitely on our agenda moving forward and we are also hoping to entice brewers from all around the world to try some new UK hops,” managing director Paul Corbett wrote via email.

Corbett recently returned from SIBA Beer X, the equivalent of the Craft Brewers Conference in the United States. “The feedback regarding the YCH distribution agreement from breweries was extremely positive,” he wrote. “This deal will open up more of the YCH varieties (including trial hops and cryo pellets) to UK brewers and will give them access to varieties and products which we haven’t been able to offer before.”

HOP PROFILE: CALLISTA

My understanding is that Callista and Grüngeist, sold by Hop Head Farms in Michigan but grown in Germany, are the same hop. The story behind that is for another time.

Callista is modern in most ways, with excellent agronomic attributes—easy to pick, drought and heat tolerant, and has good to high resistance to diseases. Also, take a look at the aroma description, and the amount of essential oil. However, she also shares something in common with landrace varieties, an alpha to beta ratio of less than one. That is a sign of a better quality of bitterness.

Heritage: A daughter of Hallertau Tradition and a Hüll breeding line male.

The basics: 2-5% alpha acids, 4.8-7% beta acids, 1.2-2.1 mL/100 grams total oil.

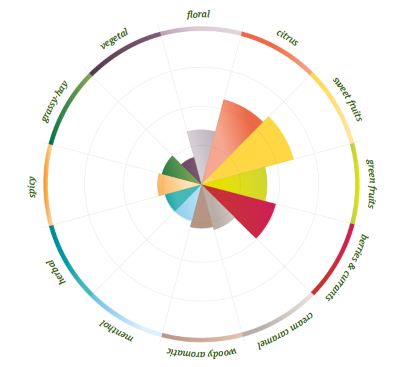

Aroma qualities: The BarthHaas 2023 Harvest Guide (see below) states: “Callista offers a fruit cocktail of berries, sweet fruits and citrus fruits, with pear, blackberry, strawberry, and black currant mixed with passion fruit, orange and caramel.” The guide points out that aromas are subdued in CY2023 Callista.

ADDITIONAL READING

– Hopsteiner has updated a list of the CO2 equivalent emissions (CO2e) of 34 hop cultivars it grows on its farms. I posted the new list along with one from CY2021 to illustrate that emissions are crop year dependent.

– The BarthHaas Harvest Guide 2023 is available to download. The guide profiles 35 hop varieties, with rose charts like the one for Calista. It also includes sensory evaluations that compare the 2023 crop to the aroma in a typical year. “Our sensory notes show that the 2023 crop’s fruity aromas are more restrained, taking a back seat to floral, woody, and minty notes,” Christina Schönberger, head of the Brewing Solutions team at BarthHaas, said for a press release.

– Thiolized Yeast 101. Laura Burns and Lance Shaner from Omega Yeast write about everything you wanted to know about thiols but were afraid to ask for The New Brewer (March/April issue).