From Vol. 7, No. 6, October 2023

There was this headline in the Washington Post: How climate change is threatening your beer. And a warning from the BBC: Climate change could make your beer taste worse. Or this suggestion from CNN that aims right at the heart: The climate crisis is coming for your hoppy beer.

There were stories in pretty much every news outlet, because of this report that predicts trouble ahead for European hops includes plenty of quotable numbers.

There is much for a hop geek to love here, particularly one interested in hop agronomics and agriculture. The authors even mention “epigenetic adaptation.”

Early on, they write, “Hop farmers can and have responded to climate change by relocating hop gardens to higher elevations and valley locations with higher water tables, building irrigation systems, changing the orientation and spacing of crop rows, and even breeding more resistant varieties.”

After that, all of the measures mentioned, and others, get more attention than ongoing efforts to breed cultivars that will produce better yields and higher quality hops with less water and despite higher temperatures. Nor do they include the newest varieties in the study. That is a serious oversight.

These varieties were not only created to survive in a less friendly future, but also have a smaller carbon footprint. They may help slow the onset of climate change. (This is true not only in Germany, but pretty much anywhere else hops are bred.)

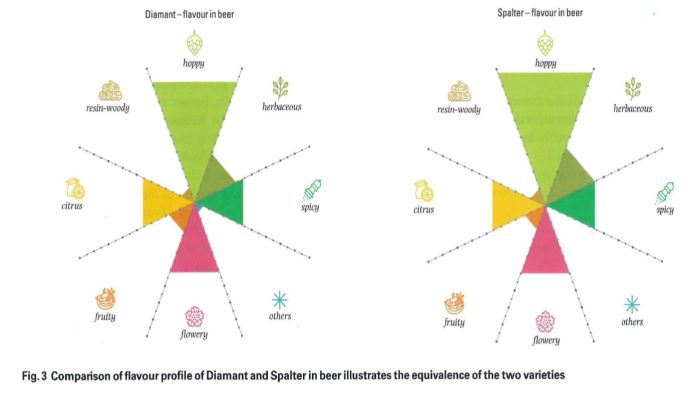

Diamant, bred at the German Hop Research Center Hüll, is one example. The hop is a daughter of the landrace variety Spalt Spalter and intended to be a Spalter replacement. Diamant has significantly improved tolerance to stress and climate, does not show “early bloom” like landrace varieties, and is more disease tolerant. Diamant yields 1,900 to 2,000 kg/hectare, while Spalter yields 1,200-1,300 kg/ha.

See how they compare in beer.

Sure looks like a hop more brewers should be using, but so far they are not embracing her. A BarthHaas dispatch reporting that 2022 hop production would be down 20 percent concluded, “We also encourage brewers to embrace modern varieties that are better suited to the changing climate and provide more stable yields than the well-known workhorses of the past.”

I have a great affection for beers brewed with Spalter as well as other landrace varieties, particularly Hersbrucker. Part of that is because they have qualities other cultivars do not. But part of it, honestly, is familiarity. There is every chance that if I had the opportunity to get to know Diamant better, say after a hectoliter or two in a high quality pale lager, I could develop a similar affection.

Always an optimist, I expect Hersbrucker & Company to be available for a long time. They might become niche varieties, more expensive for brewers to use and drinkers to buy. Or, come 2050, even if that were not feasible for Spalt Spalter, the hop would live on through its daughter, Diamant. Such an result would not be terrible. This is how natural selection worked during the hundreds of years that Spalter was becoming Spalter.