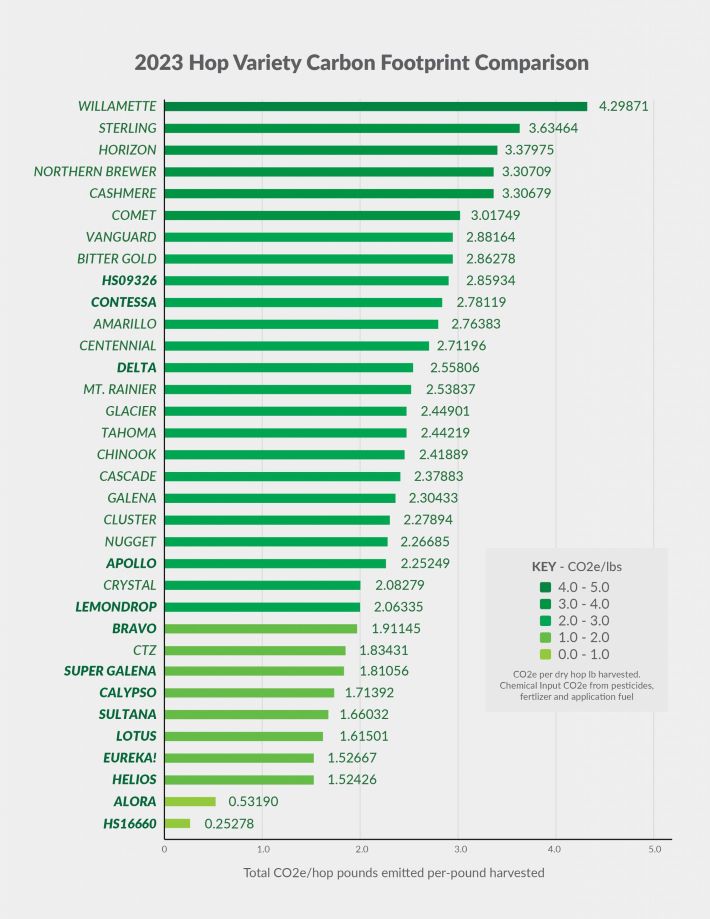

This article from The New Brewer annual raw material issue in November 2022 includes new information as well as earlier reports in Hop Queries. It includes an updated chart for the 2023 crop.

When the Hop Growers of America released an industry life cycle assessment the organization probably didn’t expect to read headlines such as, “Your Favorite IPA is Contributing to Climate Change.” After all, hops are responsible for a tiny portion of the carbon footprint of a pint of beer. In fact, producing them generates fewer greenhouse emissions and uses far less water than producing eggs of comparable weight.

“(Greenhouse gas) accounting shows that hops contribute a miniscule amount to our overall GHG footprint,” said Sarah Fraser, sustainability specialist at New Belgium Brewing. “We track their contribution but I believe it’s less than one percent and under the threshold that we have to report for our carbon neutral certification.”

Nonetheless, New Belgium considers all the factors, from the production of fertilizer and pesticides to the fuel used for drying, that contribute to CO2 emissions when selecting new varieties. “I think HBC 522 is a good example (of) a hop we’ve really like because of how it performs (environmentally),” said brewmaster Christian Holbrook. “We like it as a milder aroma hop, and growers like it as well. We will continue to look for those win-win scenarios in evaluating new varieties now and in the future, regardless of how closely we track the carbon footprint of hops.”

New Belgium previously used HBC 522 in its Voodoo Ranger beers, but she since found a home in Fat Tire, America’s first certified carbon neutral beer.

Incremental, but important

Incremental differences are still differences. Ryan Gregory, a research agronomist for Hopsteiner, turned heads at Brewing Summit 2022 in Providence, Rhode Island with a presentation that, among other things, offered a comparison between a beer dry hopped with a variety resistant to powdery mildew at four pounds per barrel versus a variety susceptible to powdery mildew dry hopped with the same quantity.

The CO2 equivalent (CO2e) emissions would be 39 percent higher in a 100-barrel batch of the beer made with a susceptible variety, generating 254 more CO2e, comparable to a 282-mile road trip.

The HGA life cycle assessment is a baseline audit encompassing the cultivation and drying of hops, transport to the processor, and the transformation and packaging of hop pellets. It provides a perspective for the industry’s environmental impact in three areas: carbon footprint (greenhouse emissions), water footprint (usage) and agricultural land usage (most of it planted).

A few takeaways from the study that illustrate how much there is for growers and breeders to take into consideration:

– Alpha and aroma hops have different footprints because of the contrast in yield, with aroma hops generally higher. 3.1 kg CO2e is generated with the production of 1 kg of alpha hops, and 3.7 kg CO2e with the production of 1 kg of aroma hops. The processing of 1.02 kg of dry whole hops into 1 kg of pellets adds .32 kg CO2e.

– 97 percent of water usage is for irrigation.

– Energy accounts for 78 percent of GHG in producing dry whole cones, with the drying process responsible for 65 percent of that. In other words, 48 percent of greenhouse gas emissions from producing dry whole cones are generated during kilning.

Sustainability has many meanings

“You don’t know how to improve something until you create a baseline,” said Jason Perrault, who wears many hats as the current HGA president. He is also CEO at Perrault Farms, and principal breeder for Yakima Chief Ranches, a partner with John I. Haas in the Hop Breeding Company, which is responsible for industry-changing varieties such as Citra and Mosaic.

He understands better than most that lowering GHG — for instance, emissions that result from kilning — may result from practices on the farm. Other reductions, for instance planting hops that are disease resistant and need to be sprayed less, will result from breeding.

“I’d like to think people see we are being proactive,” Perrault said. “We’re all multi-generational, family farms. Sustainability has always been the key for us.”

No matter which hat Perrault is wearing there are three considerations: the environmental; the social (“how we operate as a company”); and the economics (“is it positive for growers?”).

Obviously, there is crossover, and he views sustainability as a matrix. “We make comparisons between (potential) varieties based on value creation,” he said, at the moment talking as a breeder. Brewing qualities are part of the equations, as are agronomic attributes. “We may not have a line item on a chart that says carbon footprint,” he said, making it clear it is there intuitively.

Making the differences clear

Hopsteiner is in the process of completing a full life cycle assessment for its overall operations as well as for individual varieties, and as the comparison Gregory provided at the Beer Summit indicates data already compiled confirms the difference in emissions between varieties is greater than most brewers realize.

“We are talking about this because we think this is essential for the industry. There are varieties out there that need to be replaced,” said Doug Wilson, director of sales and marketing at Hopsteiner. “(Now) we have the data to show that.”

Disease resistance and yield have always been top priorities in the Hopsteiner molecular marker-assisted breeding program. Carbon footprint comparisons Gregory presented in Providence and a Hopsteiner online webinar in June indicate how successful and how important that is.

In the webinar, Gregory provided a comparison for beers that might be brewed with Helios and Sultana versus beers brewed with CTZ and Centennial. Each recipe called for 20 IBU from a 60-minute addition (Helios and CTZ) and two pounds per barrel of dry hops (Sultana or Centennial). The CTZ/Centennial recipe would produce 515.4 pounds of CO2e per 100 barrels brewed, compared to 299.9 from the Helios/Sultana recipe. The difference is equivalent to a 238-mile car trip.

“We are finding most people have never thought of their hops this way,” Wilson said. “We have customers who say, I have to have this variety. I’ve been using this variety for this long. This is more about starting the discussion.”

Breeding for the future

The hop genome is larger than the human genome and hops don’t always adhere to the principles of inheritance that Gregor Mendel outlined in the nineteenth century. “This why there is all this stuff on the board behind me,” said Nicholi Pitra, lead scientist variety development and bioinformatics, referring to a white board full of words and diagrams.

He and Gregory were talking at the moment about water use efficiency and heat stress, which should be top of mind for any brewery that uses Saaz or German aroma varieties after the disappointing 2022 harvest in Europe.

In recent years, Hopsteiner has dispatched teams around the world to collect hops growing in the wild, preserving genetic diversity.

Some, such as those found in the southwest, have survived in arid conditions “It is one thing to find one that grows on a hill . . .,” Gregory said. It is another to find one that will produce cones with qualities brewers expect.

Those plants, instead, are useful for breeding. He conducted a heat stress test on Lotus, which was bred using a wild hop from the southwest, when a heat dome settled over Washington last year and the plant’s yield decreased only 12 percent even though available water was reduced 36 percent.

Breeding clearly is one way for the industry to reduce its carbon footprint, even if line items are added to the checklist for what makes a “perfect hop.” “It’s only longer by our own design. The more we learn, the more is possible,” Pitra said.

Beyond the farm

After commissioning a life cycle assessment by an outside firm in 2019, Yakima Chief Hops determined 63 percent of CO2e come from the farm. “We viewed this as an opportunity rather than a shortcoming,” said Levi Wyatt, corporate social responsibility manager.

The company – which, of course, operates across a spectrum that includes farming, processing, packaging and shipping – has set a goal to reduce carbon emissions across its operations by 50 percent. The targets for 2025 include:

– Utilizing 100 percent renewable energy.

– Improving energy efficiencies by 5 percent annually.

– Switching to cleaner fuel and energy options whenever feasible.

– Increasing close-the-loop technology to become self-sufficient in CO2 production.

– Reducing waste 5 percent annually.

– Reducing water consumption 5 percent.

Those objectives are integrated with YCH’s Green Chief, a best practices program for growers coordinated in partnership with Yakima Chief Ranches. The practices continue to evolve, influenced by information farmers provide through an online portal. “We (YCH) are grower owned,” Wyatt said. “Let the growers lead.”

During a presentation at Hop & Brew School in September, Wyatt offered examples of how breeders provide new cultivars with the potential to lower carbon emissions. They may make processing more efficient by breeding varieties with picking windows outside of already full ones or varieties that store better and can be processed later. In 2020, YCH used 13,000,000 kwh energy processing hops and in 2021 reduced that to 11,800,000 kwh. The reduction was comparable to driving across the country 600-plus times.

Like Hopsteiner, Wyatt pointed to differences between varieties. In 2021, Cascade yields averaged 1,675 pounds an acre and Ahtanum 2,550. Total inputs (including water and chemicals) for Cascade were 32,911 gallons per acre, compared to 3,087 for Ahtanum. As a result, per acre CO2e for Cascade was 167,846 kg, more than 10 times the 15,744 for Ahtanum.

In 2021, Centennial yields averaged 1,573 pounds per acre and Ahtanum 2,800 pounds. Total inputs per acre for Centennial were 25,662 gallons, compared to 787 for HBC 522. Per acre CO2e for Centennial was 130,907 kg, more than 30 times the 4,013 kg of HBC 522.

Are brewers paying attention? “In our experience, brewers are interested in the information and want to support the general notion of sustainability. But, it’s a very rare brewer/brewery that will actually let this influence what varieties they use,” said Indie Hops co-founder Jim Solberg.

Unfortunately, that is true in Europe as well as the United States.